Summary

Phonology

Phonology

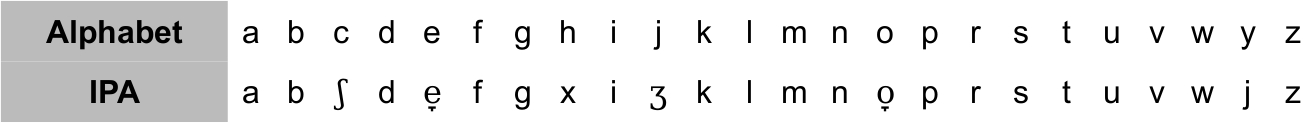

The writing system used is the latin script *, except for Q and X. Here are the letters and their equivalent in the IPA:

In Mundeze, there is a nearly one-to-one correspondence of letter to sound.

* There is a proposal for a new alphabet alongside the latin script: the alfare.

The stress always falls on the syllable preceding the grammatical ending, so generally on the last syllable of the word root.

Syntax

Syntax

The allowed word order typologies are SVO and OSV.

Mundeze is a head-final language (the complements precede its head) and it uses prepositions.

Mundeze can be spoken with ellipsis. That means that parts of the sentence may be omitted, if the context is clear.

- Example: tie atake; daví ola pagile = That — attack; give all money

(titie si bankatake; voy daví ola voya pagile na me = This is a bank robbery; give me all your money!)

Gender and number

Gender and number

– Mundeze doesn’t distinguish between masculine and feminine nouns. Gender is indicated by the prefix ba- (masculine), ma- (feminine) and za- (genderqueer).

– To put a noun in the plural form, you can add a –y at the end of the word (after -e), but it is not mandatory.

– Adjectives and adverbs show no agreement.

Parts of speech

Parts of speech

In Mundeze, all words have an invariable root, the radical, from which you can form substantive, verb, adjective and adverb.

The nouns end in -e, verbs in -i, adjectives in -a and adverbs in -o.

Example with “pel-” (to speak)

pele: speech

peli: to speak

pela: oral, verbal, speaking

pelo: orally, verbally

Pronouns

Pronouns

– The personal pronouns are:

There is also ane (one -indefinite pronoun).

It is of course possible to specify the gender, adding the appropriate prefix: malo = she

– The adjectives and possessive pronouns are formed by adding the adjectival suffix -a to the pronoun: tua = your, yours

Articles

Articles

There is no article. However, the indefinite nature can be indicated with the adjective ya (some, any), just like definite nature can be indicated using adjectives like tia (that).

tabula-leksey

tabula-leksey

Mundeze uses a system inspired by the “tabel-vortoj” of Esperanto to easily produce correlatives and other function words.

Conjugation

Conjugation

Verb conjugation is done optionally with adverbs:

There are also 3 adverbs to precise aspect. They are placed just before the verb:

- jo: for an accomplished action = perfect aspect

- so: for an ongoing action = progressive aspect

- vo: for a planned action = prospective aspect

The jussive mood (imperative) is obtained by placing the stress on the last syllable, the one of the verbal ending.

Example with “pel-” (to speak)

noy peli = We speak

noy pretempo peli = We spoke

noy vo peli = We are going to speak

pretempo noy vo peli = We were going to speak

noy pelí = Let’s speak

Sentence forms

Sentence forms

Interrogative

Interrogative

To form a question (direct or indirect), you can either add “ki” (interrogative particle) at the beginning or end of the clause, or use interrogative words (which are also at the beginning or end of the clause). Interrogative words can be preceded by a preposition.

Examples:

ki lo nyami? / lo nyami ki? = Does he eat?

– ha, lo nyami = Yes, he eats.

– ne, lo guli = No, he drinks.

kias lo ne nyami? / lo ne nyami kias? = Why doesn’t he eat?

– as lo ne gwiri = Because he is not hungry.

kie tu nyami? / tu nyami kie? = What do you eat?

– me nyami apole = I eat an apple.

kon kian tu nyami? / tu nyami kon kian? = With whom do you eat?

– me nyami kon mea basere = I eat with my brother.

me tsivoli ki lo nyami / me tsivoli, lo nyami ki = I wonder if she eats.

me tsivoli kie lo nyami / me tsivoli (ti) lo nyami kie = I wonder what she eats.

Negative and affirmative

Negative and affirmative

To form a negative sentence, we just add “ne” (no, not) before the word we want to negate. To emphasize an affirmative sentence, we just add “ha” (do, yes, indeed) before the word we want to emphasize.

Example

me ne kanti = I don’t sing

ne me kanti = I am not the one who sings

me ha kanti = I do sing

ha me kanti = I am really the one who sings

Morphology

Morphology

In Mundeze, we can easily create new words by combining roots, using juxtaposition. The root is the part of a word that precedes the grammatical ending. For example, in buke (book) the root is buk-, and the -e is the grammatical ending that indicates a noun.

Mundeze is a head-final language, which means that the complements precede its head. That applies to the words order at the sentence level, but also to word composition (for compound words using more than one lexeme)

Examples

From anar.e (group) and of.e (work), we can create:

anarofe (anar–of.e) = group work

ofanare (of–anar.e) = working group

In Mundeze, root agglutination allows to create many words, but almost all morphemes have a meaning by their own, so it is almost possible to use Mundeze like an isolating language.

For example, the locative morpheme en (in, at…) can be used as follows:

- Locative preposition: en dome (at home)

- Verb: eni (to be located in/at, to stand in/at)

- Noun: ene (place, location)

- Locative suffix: panene (bread’s place = bakery)

- Locative relative pronoun: premí en ayifi (press where it hurts)

- Locative morpheme: kien, tien (where, there)

Even grammatical endings have a meaning when isolated:

- swela energie (solar energy) = energie a swele (energy of the sun)

- tu hwinko nyami (you eat “pigly“) = tu nyami, o hwinke (you eat like a pig)

- cesí buke (take a book) / cesí, e tu voli (take what you want)

- foba myawe (a frightened cat) = myawe, a fobi (a cat who is afraid)

- me analizi (I’m analysing) = me i analize (I’m doing an analysis)

- etc.

Here is a PDF file to learn the basics of the language: DOWNLOAD